We’ve been reflecting on all this in an interview by Susanna Gevorgyan at Ius Laboris with Natália Mazoni S. Martins, Labour and Employment Specialist at the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law project [1]. Note that we have edited the text of Natália’s words for clarity, but you can also also hear extracts of the interview below.

Gender equality is a primary precondition for inclusive and resilient democratic societies. Economic growth cannot be sustainable if it is not both inclusive and green, as inequalities and shortages of resources create tension within societies. According to the OECD, to achieve sustainability, countries need to adopt inclusive and open strategies – and this naturally includes strategies that reduce inequality between men and women [2].

According to The World Bank, countries have adopted more than 1,500 reforms targeting the empowerment of women since 1971, but despite these efforts, the Women, Business, and the Law Index [3], which measures how regulations affect women’s economic opportunities in 190 economies, reveals women still don’t have equal rights with men. However, both the private and public sector recognise the gender pay gap is an obstacle to economic sustainability and are making efforts to reach gender parity.

Natália Mazoni, Labour and Employment Specialist at The World Bank, sheds light on issues relating to the gender pay gap in a conversation with us.

Susanna Gevorgyan: Natalia, first of all, thank you for joining us today. The World Bank, for almost a decade or even a bit more, has been collecting data on regulatory differences in access to economic opportunities between men and women. Fairly recently you published the ‘Women, Business, and the Law Index’ based on that data. Tell me about that Index, Natália.

Data going back to the 1970s…

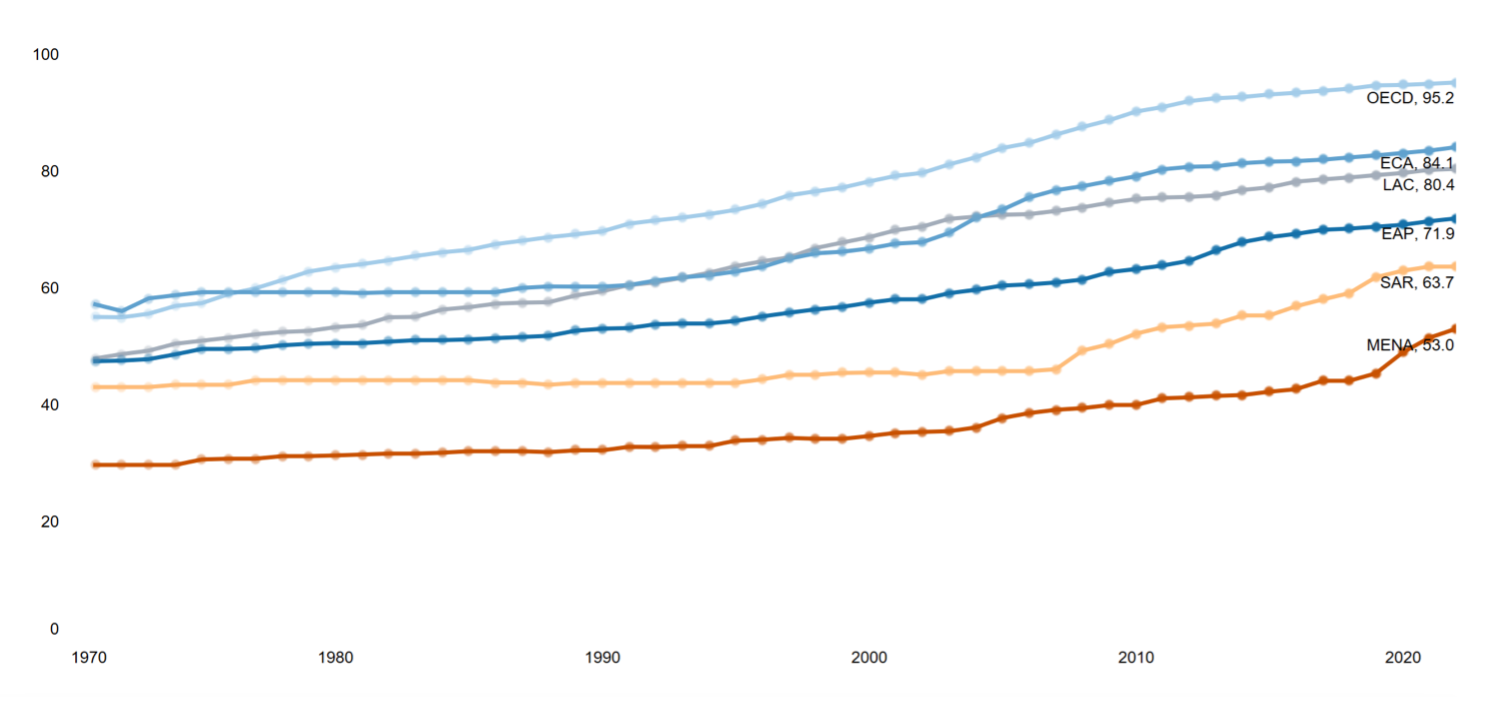

Natália Mazoni: The project measures legal and regulatory differences in access to economic opportunities between men and women. The World Bank has been collecting data for over twelve years now. However, the index was introduced only in 2020. The collected data enables us to understand the barriers, concerns, and priorities before settling an approach. So, in 2019, we had about ten years of data allowing us to observe trends, laws, and policies worldwide. Then we decided to do some historical research and go back to the 1970s. That was a big undertaking. Now with the latest publication, we have a dataset that covers 52 years of data for 190 countries.

100 means legal parity with men

Susanna Gevorgyan: Women, Business, and the Law Index consists of eight indicators structured around women’s interactions with the law as they move through their careers: Mobility, Workplace, Pay, Marriage, Parenthood, Entrepreneurship, Assets, and Pension. In the Index, the Pay indicator was the second-lowest performing. At the same time, while high-income OECD countries almost reach full pay parity with a score of 90.4, some regions, such as the Middle East and North Africa, still have a large disparity. Could you explain the pay indicator to us?

Natália Mazoni: The pay indicator measures the laws that affect occupational segregation and the gender pay gap. It has two major components. One is whether the law mandates equal remuneration for work of equal value. And the other one is whether women can work in specific categories of jobs the same way as men. So, we found that in 86 countries, women still face some form of legal job restriction. And that means, for example, women cannot work in certain industrial jobs in 69 countries. That is a huge number. Looking at the data, we can see that the gender pay gap is a reality. It’s been a reality for a long time. And what we also notice is that even when women can have the same jobs as men, they’re still underpaid. Our data shows half of the countries that we measure, 95 out of 190, still don’t mandate equal remuneration for work of equal value.

100 means legal parity with men

Susanna Gevorgyan: Natalia, every year more and more countries implement reforms targeting women’s empowerment. However, even high-income countries still struggle to eliminate inequalities between men and women, including the gender pay gap. Why is this happening? What challenges do countries face when they try to apply the reforms and what can governments do to reshape the situation?

We don’t just want equal pay law. We want equal pay…

Natália Mazoni: I think this is an essential point. We observe that in some cases, even when countries have great policies or a provision that mandates equal remuneration, the gender pay gap still exists. There’s still a lack of women’s representation in leadership positions. There’s still low participation in the labour market. We don’t just want an equal pay law; we want equal pay in practice. So, we conclude that the law alone is not enough. Then we thought about the mechanisms that need to be in place so the law can be adequately implemented. Related to the pay gap, currently, one of the aspects we are looking at is if there are ways transparency measures can address it. For instance, pay gap reporting by employers or equal pay audit certification programmes. Also, gender-neutral job specification systems and unbiased recruiting processes are essential in bridging this gap. We’re looking at that now, but unfortunately, we don’t have the results for this yet.

Susanna Gevorgyan: What can the private sector do in this situation? How can companies support governments in reducing the gender pay gap and inequalities between men and women?

A lot can come from the private sector…

Natália Mazoni: If you look at corporations, they are very good at establishing best practices aligned with good international practices. I would love to see this trickling down to smaller businesses, so as to be more equalised within the private sector. For instance, what I have just mentioned about wage transparency measures, a lot of that can come from the private sector. Companies can review and report on their internal practices, such as HR practices, including practices targeting transparency. Transparency is essential. I can’t advocate for my right as a woman, as a worker, if I don’t know what my right is. I know my value; I know my worth. But if I don’t know how my peers are being compensated and how much my work is valued within the company, then I can’t advocate for my rights. So, a lot of this requires ‘big will’ from corporations. Of course, laws and regulations help create an environment, but policies alone are not enough.

There have been many new measures and actions to reduce the gender gap in different countries in recent years, yet the gender pay gap is still a reality. Women continue to occupy lower-paid, lower-skilled positions whilst carrying out at least 2.5 times more unpaid work than men. With the current rate of progress, it will take 132 years to reach full gender equality. It’s clear that policies and regulations alone are not enough, and that proper mechanisms and norms need to be put in place by governments to reach better results. At the same time, it’s clear that the private sector can play a key role in fighting gender inequality by implementing transparency measures and taking concrete actions against gender inequality and the pay gap.

Discover our equal pay series page for related insights

[1]https://wbl.worldbank.org/en/wbl

[2]OECD, Inclusive green growth: For the future we want (2012)

[3]https://wbl.worldbank.org/content/dam/sites/wbl/documents/2021/02/WBL2021_ENG_v2.pdf

For more information about gender pay gap