The Pay Transparency Directive will require employers throughout the EU to implement gender pay gap reporting and comply with new, tougher pay transparency requirements. It must be implemented by all EU member states by June 2026. The Pay Transparency Directive introduces a requirement to carry out a ‘Joint Pay Assessment’ where gender pay gaps within any category of worker are greater than 5% and this cannot be justified. In this article, we take a closer look at Joint Pay Assessments and discuss how EU employers can prepare for this aspect of the Pay Transparency Directive.

The Pay Transparency Directive does not define the exact limits of a Joint Pay Assessment. Article 10(2) says that Joint Pay Assessments shall be carried out ‘in order to identify, remedy and prevent differences in pay between female and male workers which are not justified on the basis of objective, gender-neutral criteria’.

There should be a clear objective to a Joint Pay Assessment: the elimination of gender-based pay discrimination. The Directive states that such assessments must include the following:

However, because the exact methodology of a Joint Pay Assessment must be agreed with employee representatives, the form and scope will likely differ between employers, sectors and member states.

As mentioned above, there is no set methodology for a Joint Pay Assessment. This might change as member states implement the Pay Transparency Directive over the next three years. We expect that equality bodies will publish their own guidance and recommendations for what a Joint Pay Assessment should include.

However, given the aims of a Joint Pay Assessment, they can be expected to comprise the same general structure and stages. This will include collecting relevant data and analysing it to fully understand the reasons for the pay gaps before finally identifying and consulting with worker representatives on what remedial and preventative steps are needed.

In the UK, the Equality and Human Rights Commission sets out a structure for a ‘gold standard’ equal pay audit, which is broadly similar to a Joint Pay Assessment. It has published guidance on how small and large employers (under 50 employees and over, respectively) can carry out an equal pay audit. The five-step process for large employers involves deciding the scope, determining where men and women are doing equal work, collecting pay data, identifying causes of gender pay differences, and developing an action plan. A Joint Pay Assessment focusses on the last three steps.

A Joint Pay Assessment is required if all of the following conditions are met:

Categories of worker, in this context, means workers who do the same work or work of equal value. The intention is to tie in with the comparison that can be used for the purposes of an equal pay claim under EU law. We’ve written more about putting workers into categories in our Pay Transparency Directive FAQs.

The recitals to the Pay Transparency Directive (while technically not binding) state that whether or not a pay difference can be justified is something that must be agreed with workers’ representatives. Whether or not something is objectively justified may be disputed. What if the workers’ representatives and employer do not agree on whether something is objectively justified? Does this mean that the representatives can effectively hold the employer to ransom and force it into a Joint Pay Assessment? Or might member states give employers a right to, in effect, appeal against their workers’ representatives to a competent labour authority or court to determine whether a pay difference is objectively justified? The answer is likely to depend partly upon how the Pay Transparency Directive is implemented in each member state, and also upon existing systems and bargaining processes.

Under the Pay Transparency Directive, ‘pay’ means ‘the ordinary basic or minimum wage or salary and any other consideration, whether in cash or in kind, which a worker receives directly or indirectly (complementary or variable components) in respect of his or her employment from his or her employer’. Pay is to be interpreted in line with the caselaw of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

The CJEU has answered many preliminary questions on what counts as ‘pay’, which the CJEU has interpreted broadly. In those cases, pay has included not only basic pay, but also, for example, overtime supplements, special bonuses paid by the employer, travel allowances, compensation for attending training courses and training facilities, termination payments in case of dismissal and occupational pensions. Benefits in kind are also included. We explain this further in our Pay Transparency Directive FAQs.

CJEU definition vs member states’ definitions of pay

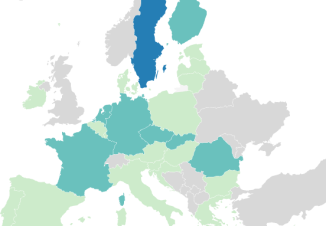

At the EU level there is a clear and broad definition of pay in the equal pay context. In theory, this definition must be mirrored locally in all member states. However, a recent comparative analysis of gender equality law in the EU has shown that this is not the case in practice.

There are a number of countries in which ‘pay’ is not clearly defined (such as Austria, Italy, Sweden, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Latvia) or where there is no single and exhaustive definition of pay provided for (as in Belgium).

In the Netherlands, the definition of ‘pay’ in national law is less broad than in EU legislation. Similarly, although the Romanian constitution sets out a right to equal pay, this only applies to ‘like work’ and not ‘equal value’ cases; the definition of ‘pay’ is narrow and applies only to salary, rather than other types of remuneration.

Interpreting pay when preparing for Pay Transparency Directive

This difference between the established EU definition of ‘pay’ and the existing local interpretation adds extra complexity for employers considering how best to prepare for the Pay Transparency Directive.

Employers looking to do early analysis now and identify whether they currently have pay gaps greater than 5% in any category should be wary of adopting too narrow a definition of ‘pay’ in their calculations. For example, if an employer neglects to consider benefits in kind (as seemingly required by the Pay Transparency Directive) then this may result in an apparent pay gap under 5% but a ‘real’ or ‘reportable’ gap of above 5% once valuable benefits (such as a company car) are factored in.

Any early assessment should take these subtleties into account. We suggest analysing data in a way that both includes and excludes different pay elements. This will give greater assurance as to whether there are any real equal pay issues.

Article 10(2) of the Pay Transparency Directive says that a Joint Pay Assessment must be carried out by employers in cooperation with workers’ representatives. This cooperation is why it is called a ‘joint’ pay assessment. If there are no workers’ representatives, some must be chosen.

The Pay Transparency Directive does not say how many workers’ representatives must be involved, nor how they should be chosen besides being ‘designated by workers for the purpose of the joint pay assessment’ and ‘in accordance with national law and/or practice’. This suggests that any existing elected representatives cannot necessarily be co-opted into also being representatives empowered to take part in a Joint Pay Assessment. For example, health & safety representatives might be unlikely to have sufficient authority to perform the role. Instead, there must be a mandate.

This could mean that, in future, ‘dealing with Joint Pay Assessments’ might be included within the range of responsibilities of a representative under the terms of a works council agreement or national legislation on works councils.

Of even greater significance, and independently of pay gap issues, this new requirement for workers’ representatives might lead to a radical change in how some employers engage with their workforces. For example, employers may not want to engage with new workers’ representatives on each Joint Pay Assessment. The Pay Transparency Directive may therefore lead to the creation of standing bodies of workers’ representatives for the first time at some employers and, with it, the possibility of future ‘mission creep’, with those representatives assuming a more significant remit over time. This could permanently change an employer’s ‘employee voice’ architecture.

Employers may need to liaise over technical analyses of pay with workers’ representatives who lack knowledge or experience of either equal pay laws or statistical analysis. Employers should therefore consider providing training and other support to them, in order to streamline the process and mitigate any future friction.

Joint Pay Assessments will be triggered when there is a gap greater than 5% in any category of worker. Calculation of this gap will be relatively simple – it will be a case of identifying the average for women within a category and then comparing this to the average for men.

But once the Joint Pay Assessment is required, the statistical calculations may become more onerous. You will be trying to understand what factors are driving the pay differentials, the extent to which those drivers are directly or indirectly influenced by gender and whether or not your pay drivers are legally justifiable.

The problem with simple averages when looking at potential equal pay issues is that they can mask individual cases and hide outliers. Fundamentally, they do not actually allow an employer to ‘get under the bonnet’ of what is driving pay and whether those factors are legally justifiable.

To properly analyse potential equal pay issues, other statistical approaches may be useful, for example:

Employers should consider using these statistical techniques (and more – Machine Learning techniques can be powerful) when preparing for the implementation of the Pay Transparency Directive.

Statistical analysis is vital to help you understand what factor or combination of factors are influencing pay – and whether the factors you thought were influencing pay are actually doing so. You will also need to investigate if your pay differentials are gender biased. This is the essential point of both working out whether a Joint Pay Assessment is required; and the Joint Pay Assessment itself.

Caselaw has established that a wide range of factors can lawfully account for pay differentials between employees doing like work or work of equal value, including variations in experience, geographic location and performance, and whether or not any relevant population has been transferred on protected terms. If a factor is ostensibly gender neutral, but in practice tends to put one gender at a disadvantage, then it also needs to be justified as a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. This will involve having to show the purpose and proportionality of the link between pay and the factor in question. It is a complex analysis, and further demonstrates the need for employers to get to grips with their gaps and the reasons for them early on.

If there are differences in pay which cannot be justified, the Joint Pay Assessment must include a plan to remedy this within a reasonable timescale. In this sense, the Joint Pay Assessment involves a form of pay bargaining with the workers’ representatives. The action plan will very much depend on the circumstances, but might include, for example, new pay review processes, manager training, new processes around pay rises following family leave (if taking family leave is shown to disadvantage women in terms of pay progression) and reduced manager discretion around variable pay.

The Joint Pay Assessment has to be published to workers and made available to equality bodies and labour inspectorates upon request. This level of transparency will be a concern for employers if the Joint Pay Assessment has exposed significant potential equal pay issues, leaving the employer open to litigation or potential enforcement action.

Joint Pay Assessments effectively open up your pay structures and processes to workers and their representatives. They have the potential to be difficult, onerous and expensive and carry the risk of attracting litigation and enforcement action. Employers will want to avoid them where possible. Key to achieving this will be an early assessment of the risk of having to report gaps of greater than 5% in any category of workers, so that you have time to bring the gap below the threshold ahead of mandatory reporting. The first reports are not due until June 2027 (unless member states implement ahead of the deadline), but pay gaps can be stubborn and slow to change. It’s best to start early with your preparation.

To find out more about anti-discrimination law