The Pay Transparency Directive will require employers throughout the EU to either implement gender pay gap reporting for the first time or, in countries where it already exists, broaden the scope of the requirements. Employers will need to report the gender pay gap:

The Pay Transparency Directive also creates a number of individual rights to pay transparency. It requires employers to advertise the salary range for each job vacancy and to stop asking job applicants about their current and past pay. All workers will have a new right to request information about what others doing comparable jobs are paid, on average, which essentially means that employers will need to respond to requests for information for relevant equal pay statistics.

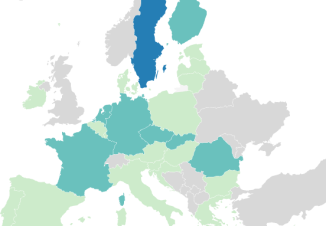

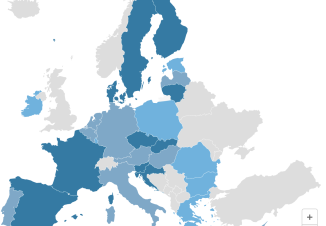

The Directive builds on the growing body of pay transparency laws already in place across Europe. For example:

For more detail about gender pay gap reporting requirements across Europe see at our at-a-glance gender pay gap reporting map.

The gender pay gap reporting requirements will initially apply to all employers with at least 150 employees, dropping to 100 after four years. Those with 250 or more employees will have to report gender pay gaps annually, while others caught by the Pay Transparency Directive will have to report every three years.

Assuming that EU member states implement the Pay Transparency Directive on time, employers with at least 150 employees will need to compile gender pay gap reports for the 2026 calendar year. Employers with at least 100 employees will start gender pay gap reporting in relation to the 2030 calendar year. Those with less than 100 employees will fall out of scope of the Pay Transparency Directive’s gender pay gap reporting requirements but may of course be caught by local pay reporting regimes.

When counting numbers of employees, you look at each individual employing company, rather than a group of companies as a whole.

Crucially, it’s important to note that there are no size thresholds for the other pay transparency rights in the Pay Transparency Directive. All employers, irrespective of size, will need to comply with the salary history ban, obligation to advertise salary ranges and requirement to supply information on what comparable employees are paid upon request. Those rights (explained in more detail below) will take effect as soon as the Pay Transparency Directive is put into local legislation – which must happen by June 2026.

The Pay Transparency Directive applies to all types of employer. This extends to employers of record, although the data they report may be less meaningful unless they have set up individual entities for each of their clients.

For HR, in-house employment lawyers and other people professionals with responsibility for compliance, the initial priority is to get the Pay Transparency Directive on the business agenda as early as possible. This is likely to involve spelling out the risks of a breach while articulating the potential gains to be made through compliance, such as improved standing among customers, job applicants and existing employees by taking pay equity seriously. You will need to assemble a project team, which is likely to draw people from operational, technical, legal, HR, reward and benefits teams.

Given the depth of data that you will need to publish, and the potential for it to be tested and analysed by employee representatives (and their advisers), it will be important to be upfront and honest, but also to have a positive message about any improvements that might be needed. A proactive and successful communications approach will reduce the chances of data being subjected to hostile interrogation, either by the media or workers’ representatives.

The Pay Transparency Directive requires gender pay gap reporting by ‘categories’ of worker, which is defined as meaning workers who do the same work or work of equal value. The intention is to tie-in with the comparison that can be used for the purposes of an equal pay claim under EU law.

Although in theory the concept of equal value should be consistent across the EU, in reality we are likely to see different approaches to putting employees into categories. In France, the current gender pay gap reporting regime allows employers to choose between using very broad categories (e.g. blue-collar, white collar etc), the classification system adopted by the relevant collective bargaining agreement, or, after consultation with the works council, an internal job classification system. Other countries may adopt similar approaches.

How categories are defined is inevitably going to have an impact on the published results, and their comparability across jurisdictions.

Employers need to do a joint pay assessment under the Pay Transparency Directive if all three of the following conditions are met:

The pay assessment is essentially a detailed equal pay audit which is done in co-operation with the employee representatives. This is one area where the Directive bares its teeth: triggering a joint pay assessment is likely to be time consuming and risky. It requires additional data and analysis including, for example, an analysis of the proportion of male and female workers in each category, an investigation into the underlying drivers of pay differentials and a specific look at pay rises following family leave. The joint pay assessment has to be published to workers and made available to equality bodies and labour inspectorates.

You have got to publish the average gap between people doing jobs that are legally comparable and, if you end up in a joint pay assessment (see above) you will have to share more detailed data. But you are disclosing averages not specifics. There may also be good explanations for differentials. Nonetheless, this clearly comes closer to reporting actionable breaches than has been the case in many member states before, and leaves you open to further interrogation and potential litigation.

Pay is defined as including ‘ordinary basic or minimum wage or salary and any other consideration, whether in cash or in kind, which a worker receives directly or indirectly (complementary or variable components) in respect of his or her employment from his or her employer’. This definition is based on the right to equal pay which is enshrined in the EU Treaty.

This definition of ‘pay’ is broader than existing definitions used for gender pay gap reporting in the UK and Ireland since the value of benefits must also be included. Since the definition covers consideration ‘in kind’ whether ‘directly or indirectly’, it would also be broad enough to cover share awards such as RSUs and options.

In theory, pay should be defined consistently across the EU, but there is the potential for local variation nonetheless (e.g. between the UK and Ireland, overtime and statutory leave payments are not treated in the same way). There are also likely to be different approaches to calculating average pay; for example, do you take a snapshot in a particular month or look across the whole year? Countries with existing gender pay gap legislation are likely to build upon existing practice, rather than throw it out, meaning that they are likely to stick closely to their current methodology.

Employee representatives will have the right to ask for additional clarifications and details regarding any of the data provided, including explanations concerning any gender pay differentials and the system chosen for putting employees into categories. Employee representatives also have a major role to play in joint pay assessments. Countries where representatives are not already in place will have to enact systems for putting them in place.

Employee representatives will not be effective in their roles if they lack essential knowledge. They could end up delaying or frustrating efforts to achieve compliance if they are not upskilled. It will be in an employer’s best interests to provide employee representatives with training on the requirements of the Pay Transparency Directive (and local implementing legislation) and ensure they are statistically confident.

There is much to be learned from the UK experience of gender pay gap reporting. In the first couple of years, there was a lot of misunderstanding as to what the statistics were saying. A high pay gap doesn’t mean there is an equal pay issue (and vice versa). A worsening pay gap doesn’t necessarily mean an employer isn’t trying hard to improve gender equality – if a large cohort of entry level women join a formerly male dominated workplace, this will exacerbate reportable gaps in the short term but in the long run reduce gender pay gaps. Beside these statistical issues, the complicated technicalities and definitional quirks of the Regulations can be a struggle for the unfamiliar to get their heads round.

In France, employee representatives have a right to be assisted by experts. Where possible, training representatives yourself and building trust is likely to be preferable to offering access to advisers and experts.

The Pay Transparency Directive creates several new individual rights to pay transparency, including:

Note that the definition of pay here includes discretionary and variable pay. These new rights therefore look set to expose discretionary bonuses to greater scrutiny.

It remains to be seen if countries will enact specific legislation or publish guidance on this point. In New York State, which recently imposed a requirement to advertise ‘good faith’ salary ranges, several employers came in for media criticism for publishing overly broad ranges although it is too soon to assess what longer-term norms will emerge. Some argue that companies put themselves at a disadvantage by publishing a very wide range, as they could be unnecessarily deterring candidates by the low number while disappointing others who are not offered the highest.

Sanctions for failing to report gender pay gaps or breaching the individual pay transparency rights are likely to vary by country. The Pay Transparency Directive makes clear, however, that a breach of any of these requirements will shift the burden of proof to the employer in any equal pay claim. This means that, if an employee brings an equal pay claim against an employer that has failed to comply with a requirement of the Pay Transparency Directive, the employer will have to prove that there was no direct or indirect discrimination. There is an exception if the breach was ‘manifestly unintentional and of a minor character’. The Pay Transparency Directive also requires member states to ensure that equality bodies and other representative groups can bring equal pay claims on behalf of, or in support of, employees.

The EU likes to see itself as a global leader in regulation, setting the standards to be followed elsewhere, and it has certainly achieved a degree of success on that front (especially with the GDPR). It is reasonably likely that other legislators across the globe will adopt EU-style legislation on gender pay gap reporting. It’s also likely that some multinationals will choose to apply the requirements globally, including, for example, the salary history ban and practice of advertising pay ranges.

The obligation to calculate and report gender pay gaps by category is the biggest potential issue for employers. If gaps are greater than 5%, not only can it lead to a mandatory joint pay assessment, but it also flags potential equal pay issues and creates an open goal for any litigious employees or trade unions.

We recommend doing a dry run along the following lines:

To get ready for the other individual rights, we also recommend:

To find out more about gender pay reporting