It’s been the perk employees have consistently demanded, but not always achieved: more scope to work from home. But with many workers now approaching their first full year of home working, due to the coronavirus pandemic, cracks are starting to show. Isolation, reduced personal contact and increased blurring of home-work life is now creating a brand-new epidemic, one of ever-worsening mental health. Of course, not all of this should be attributed to work, as there are many factors leading to people’s increased stress levels at the moment, but work factors are surely playing a significant part.

In the UK, the Office for National Statistics reports 19.2 per cent of adults are now suffering from some form of depression, up from 9.7 per cent pre-pandemic. While in Europe as a whole, 62 per cent of staff report greater levels of stress, with 81 per cent describing themselves as having a “low” or “poor” state of mind, according to AXA: A Report on Mental Health and Wellbeing in Europe, which polled 5,800 people in the UK, Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. Globally, the Institute for Fiscal I Studies says 7.2 million more people are suffering from mental health problems “much more than usual”.

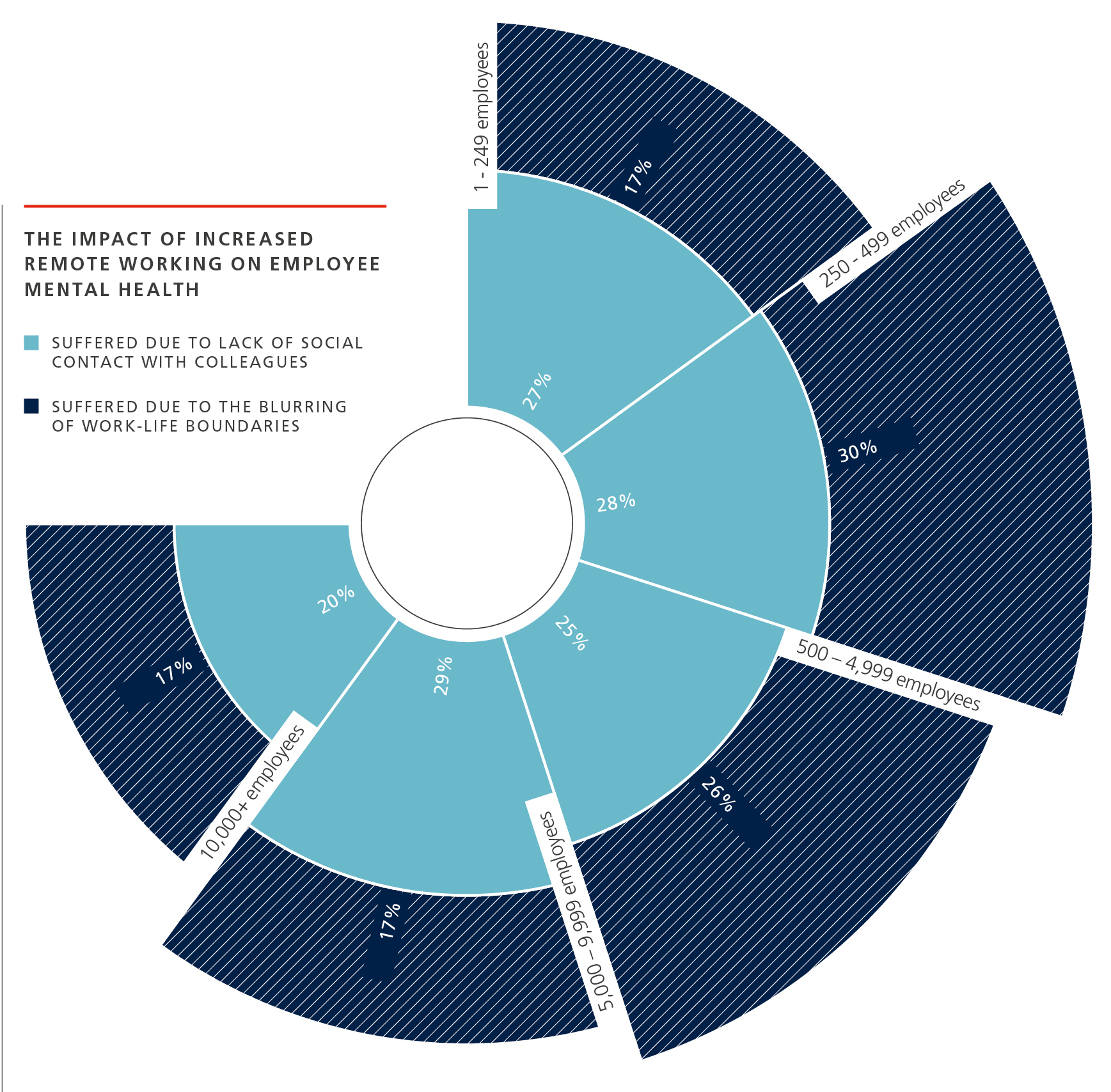

But while big businesses have led the way in implementing videoconferencing platforms, wellness programmes and resilience training in an attempt to mitigate this, it seems the majority of the world’s employees, who work for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), are missing out. Ius Laboris data finds that while 23 per cent of firms with 5,000-plus staff increased provision of mental health initiatives, barely one in ten (11 per cent) of SMEs have. And it’s starting to show as 30 per cent of businesses with 250 to 499 employees say their employees’ mental health has been negatively affected.

“Smaller businesses obviously lack the resources larger firms have,” says Ali McDowall, leading mental health campaigner and co-founder of The Positive Planner, itself an SME. Adding to this, Erica WolfeMurray, international SME adviser and author of Simple Tips, Smart Ideas: Build a Bigger Better Business, notes: “Just as relevant is the fact that many SMEs either lack expertise in this area or feel because they are small and know everyone already, it’s simply not needed.”

According to Wolfe-Murray what’s particularly difficult for SMEs is knowing what their legal responsibilities are around protecting their employees’ mental health. She says: “Mental health falls between legislative gaps and tends to feature indirectly in most countries’ health and safety legislation.

Often it is not labelled as mental health at all, but is couched in terms of anti-discrimination law, gender pay reporting or workingtime laws, the absence of which could lead to people reporting suffering undue additional stress, anxiety or mental health problems.” Requirements of workplaces to make adjustments to avert any mental health escalations include ensuring correct workstation setup, which addresses physical injury first, but nods to the fact it could cause mental ill-health problems if physical symptoms persist. Broader rules, such as those contained in the UK Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1992, require employers to assess mental health work-related issues from the point of view of potential risk to staff.

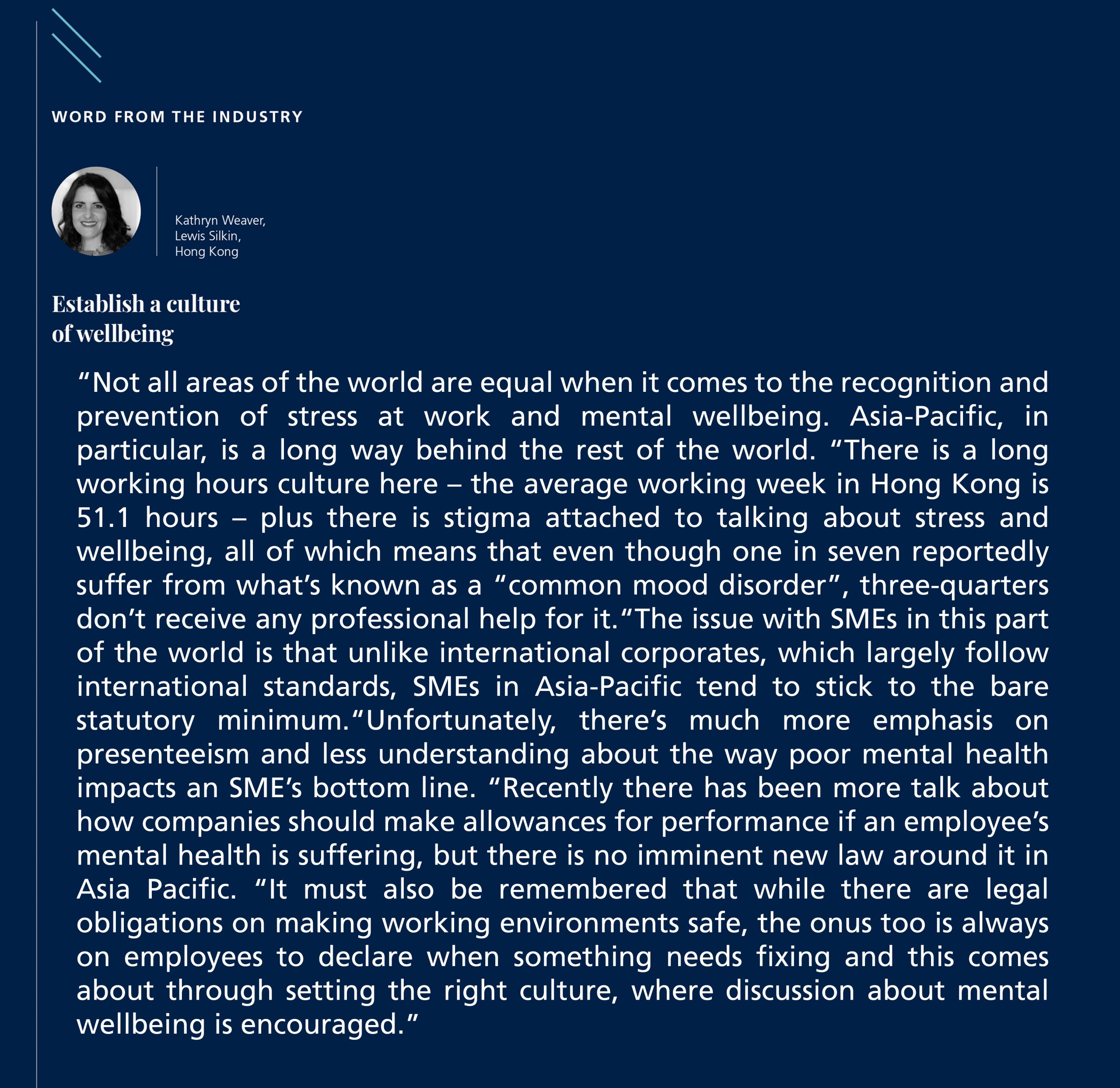

This may include things that could cause staff to experience work-related stress, such as overworking, inadequate training, harassment or job insecurity. Most countries have their own equivalents, such as Hong Kong’s Occupational Safety and Health Ordinance (refer to ‘Word from the Industry’ box on page 31), or the European Union’s Health and Safety Framework Directive, which requires EU member states to implement domestic law requiring firms to “evaluate occupational risks specific to job type and provide adequate protective and preventative services”.

In the United States the dominant legislation is the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act, which protects citizens from discrimination at work, but also against mental health problems being left untreated, if it hampers their ability to do their job.

But Kathryn Weaver, Ius Laboris firm Lewis Silkin Hong Kong’s head of employment, says globally mental health remains a vague definition. “The issue with mental health is that it’s impacted by so many variables – some people thrive on stress, others don’t – and so the causality of mental health issues is difficult to prove. The areas of law it is linked to are personal injury and disability discrimination and people complain that the law isn’t drafted adequately to cover mental health, but legally it is tough to draft anything more specific, as it then becomes too prescriptive,” she says.

Attempts to enshrine something more concrete are emerging though. Irish MPs recently proposed private members’ bills requiring employees to have a statutory “right to disconnect”, which has echoes of similar law already enacted in France. The EU Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions and the Work-Life Balance Directive have both been approved and must enter into member states’ national law by 2022.

But while ad hoc laws have been passed, such as 2016 regulations by the Swedish Work Environment Authority looking at employees’ social and organisational work environment, specific mental health law is lacking. Under Danish law, for example, there is an obligation for employers to ensure a healthy and safe work environment in general, but there is no specific regulation of mental health. Since the pandemic started though, a more concerted effort by unions, European Trade Union Confederation and Eurocadres to lobby the EU has been made to redress this, with the launch of the EndStress.

EU campaign in October to specifically legislate for preventing stress. Eurocadres president Martin Jefflén says: “Only a handful of EU member states have legislation on work-related stress and just a third of workplaces have an action plan to prevent work-related stress. We need a separate directive to address the stress at work epidemic, just like there are for many physical risks.

Health and safety laws can be incredibly efficient, but the EU legal framework from 1989 is not good enough.” Michał Piórkowski, founder of Polish-based SME Visuality, which employs 30 people, says mental health still doesn’t have visibility beyond standard health and safety laws. “For us, we’ve always been very clear about organising work so people’s mental health is protected,” he says. “Because we’ve built ourselves around our culture, I was immediately worried about how it would be impacted by home working, because when you lose the office, and the vibe, the culture can go very quickly. “We immediately began more monitoring; we put in pulse surveys asking people how they were feeling and we structured in non-work time, where people could just talk to each other. We brought in a videoconferencing platform called ZING, which also has games people can remotely join in with.”

Piórkowski continues: “We’re very sensitive to hearing people’s personal problems, but beyond complying with minimum health and safety, this is not normal in Poland. Entrepreneurs don’t tend to want to involve themselves in people’s personal lives.” Jimmy Williams, co-founder and chief executive of insurance company Urban Jungle, says: “Remote-working SME employees feel mental health effects more because of all the very best things about SMEs, that they have a tight-knit sense of belonging and camaraderie.

But that’s not a reason to just stick to the bare minimum. When working apart removes this, SMEs have to work doubly hard.” Melissa Robertson, chief executive of 45-strong sports marketing agency Dark Horses, adds: “We made a very conscious effort to speak to staff about their life and what was impacting it. But as we spotted the signs of loneliness and possible mental health strain in meetings, we immediately looked into specific interventions, including signing people up to online counselling, employee assistance programmes, and to Vitality Health, where staff can monitor their own mental health. “Change does only tend to happen when there is legislation.

SMEs will be less inclined to make changes unless they are made to.” In response to rising incidents of poor at-work mental health pre-pandemic, a new global ISO standard around preventing stress was already being worked on – ISO 45003 – which is scheduled to be announced this summer. It builds on existing ISO 45001 accreditation for managing health and safety in the workplace that requires firms to design management systems to report at-work risk.

The new ISO 45003 standard establishes the term “psychosocial risk” and will require firms to look at how risk relates to the way work is organised. The assumption is that psychosocial hazards are present in all organisations and sectors, and from all kinds of employment arrangements. Stavroula Leka, professor of work organisation and wellbeing at Cork University Business School, and co-convener of the working group developing ISO 45003, says: “ISO 45001 is a generic management system standard for health and safety, and doesn’t go into any specific areas of risk.

But with mounting data that poor work organisation, design and management is associated with poor mental health, absenteeism, presenteeism and human error, it was felt a specific guidance standard on psychosocial risks was needed.” Antony Eckersley, managing director at TSE Solutions, which advises on health and safety law, says: “The point we all have to remember is the fact that many companies still brush psychological health under the carpet. ISO 45003 is a proactive attempt to make good mental wellbeing part and parcel of a company’s culture.”

The new standard will be voluntary, but while some SMEs might have reservations about getting too involved in their employees’ mental wellbeing, not doing so could be taken out of their hands. “While we’ve long talked about health and safety at work, regulators and organisations have been mostly concerned with the safety side of things, while the health part has often been left behind,” says Rhian Greaves, regulatory lawyer specialising in health and safety, with Pannone Corporate.

More and more, procurement departments are now insisting firms they deal with have demonstrable measures in place for the protection of the health and wellbeing of staff, and this means SMEs will need to take seriously the stress they may be placing on their staff. If pre-pandemic was all about SMEs working out the best way to grow, post-pandemic it will also be about protecting employees’ mental wellbeing.