The new Directive on Transparent and Predictable Working Conditions in the EU (the ‘Directive’) has been passed by all parts of the EU’s legislative machinery and will shortly be published in the Official Journal. From that point, Member States will have three years, until mid-2022, to implement it into domestic law.

Background to the Directive

The backdrop to the Directive is the EU’s desire for a legislative framework capable of coping with the rapid rise of flexible, technology-enabled ways of working, epitomised by the platform or ‘gig’ economy. However, as the Directive will apply to all workers in the EU, it will have repercussions even for those operating in the most traditional of workplaces.

The Directive’s impact in the UK

Of course, no one can predict whether the UK will be obliged to comply with the Directive. In the event of a 31 October hard Brexit we can assume that it won’t, although it could have been obliged to do so on the basis of Theresa May’s proposed Withdrawal Agreement and it could potentially choose to do so as part of a commitment to keep pace with EU employment rights (which Theresa May would have been willing to make).

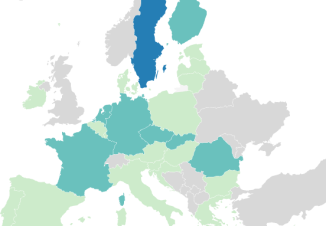

The Directive, though, will still be relevant for those responsible for managing employees in other EU countries, as they will certainly have to implement the Directive’s provisions.

It is also important to note that the UK Government said that it would take forward some of the Directive’s provisions in its December 2018 Good Work Plan. Most of that Plan is currently foundering in the Brexit quicksand, but a few reforms are starting to come through, including new requirements for written statements (summarised here) which apply from 6 April 2020 and which mostly come from the Directive.

The Directive’s application to workers as well as employees

The Directive applies to anyone considered to be a ‘worker’ under European Court of Justice case law: ‘a person who performs services of some economic value for and under the direction of another person in return for which he receives remuneration.’ There will doubtless continue to be disputes as to what ‘for and under the direction of another person’ means, and indeed the preamble to the Directive acknowledges that while on-demand, platform and intermittent workers ‘could’ fall within the scope of the Directive, ‘genuinely self-employed’ persons will not do so.

There is no obligation to apply the Directive to anyone who works an average of three hours a week or less over a period of four weeks unless that person has no guaranteed amount of paid work, in which case there is.

Ten key takeaways from the Directive

So, what will the Directive mean? Here are ten key takeaways:

1. Anyone who is a worker will have the right to receive a statement of their terms and conditions within a week of starting work. The list of required particulars for all workers and employees includes core terms such as place of work, paid leave entitlement, pay, notice and details of working pattern, including in particular whether it is predictable or unpredictable. The UK Government is already bringing these requirements into UK law from 6 April 2020, and in fact has gone further than the Directive in requiring particulars to be provided by day one.

2. Where the work pattern is entirely or mostly unpredictable, the employer must state the number of guaranteed paid hours, the pay for work performed in addition to those guaranteed hours, and the reference hours and days within which the worker may be required to work. The UK would need to legislate on this requirement and the below provisions of the Directive if the Directive is to be adopted in this country, although the Government has said it would take some of them forward as part of its Good Work Plan.

3. There will be a ban on probationary periods (which in the UK are currently entirely a contractual matter) exceeding six months unless on an exceptional basis this is justified by the nature of the employment or the worker’s interests. Absence during the probationary period will justify an extension of equivalent duration. Any probation periods in fixed-term contracts must be proportionate to the overall duration.

4. It will become unlawful to prohibit workers from taking up employment with other employers outside working hours, unless this can be justified by objective grounds such as health and safety, protecting business confidentiality or avoiding conflicts of interests.

5. Workers whose work pattern is unpredictable will be able to refuse an offer of work without suffering adverse consequences unless they are given reasonable notice and it takes place within predetermined reference hours and days as set out in their contract.

6. Workers will become entitled to compensation if their employer cancels an assignment after a specified ‘reasonable deadline’ (what this is must be decided by Member States).

7. Member States which permit the use of ‘on demand’ or similar employment contracts (not defined) must either place limits on their use or duration, or create a rebuttable presumption that it is an employment contract with a minimum amount of paid hours based on the average hours worked in a given period, or take other ‘equivalent measures’ to prevent abusive practices.

8. Workers with at least six months’ service will have a right to request a new form of employment with more predictable and secure working conditions and to receive a reasoned written reply within one month.

9. Where mandatory training is prescribed by law, the employer must pay for it, it must count as working time and, where possible, it must take place during working hours.

10. Workers who seek to exercise their rights under the Directive will be protected from adverse treatment or dismissal for doing so.