Why?

Recent scandals such as Luxleaks, Panama Papers and Cambridge Analytica have been the main driver behind the Directive. Originally, the EU Commission was against a Directive, but strong lobbying by journalists’ organisations, civil society and MEPs, coupled with the recent scandals, resulted in the Commission initiated a proposal for a Directive. This was also motivated by a desire to harmonise whistleblower laws across the EU as only ten Member States were thought to have comprehensive legal protection for whistleblowers, being : France, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Malta, Netherlands, Slovakia, Sweden and the UK.

When?

The Directive was approved by the EU Parliament on 16 April 2019 after which it was sent to the Council for final approval. After this the Directive will be published in the EU Journal giving the EU Member States two years to implement and comply with the Directive.

What?

The Directive lays down minimum standards for the protection of persons reporting on breaches of EU law.

Scope of the Directive

Under the Directive, persons may report on various breaches of EU law. These include, for example, public procurement; financial services, money laundering and terrorist financing; product and transport safety, protection of the environment; data protection and public health (Article 2). EU employment law is not covered as the EU Commission considers that there are already proper mechanisms in place to protect those claiming breaches of EU employment law (for example the possibility of bringing victimisation claims).

A ‘breach’ is defined as:

‘acts or omissions that are unlawful and relate to the Union acts and areas falling within the scope [of the Directive] or acts or omissions that defeat the object or purpose of the rules [falling within the scope of the Directive]’

(Article 6).

There are already, at an EU level, various sector specific whistleblower protections in place (e.g. financial services, money laundering etc.) and where protection is already secured by sector specific Union acts, the Directive will not apply.

Personal scope

The Directive applies to ‘reporting persons’ working in the private or public sector and who have acquired information on breaches in a work-related context. This includes workers, self-employed persons, board members, shareholders, volunteers, job applicants, people whose employment has ended, and those under the supervision or direction of a contractor, sub-contractor or supplier (Article 4).

The Directive also affords protection to ‘facilitators’ (being people who assist the reporting person); persons connected to the reporting person and who suffer retaliation in a work related context (e.g. colleagues or relatives) and legal entities that the reporting person owns, works for or is otherwise connected with in a work related context.

Conditions for protection

A person reporting on breaches will be protected if he or she has reasonable grounds to believe:

• that the information is true at the time of reporting; and

• that it falls within the scope of the Directive (Article 5).

Internal reporting channels

Under the Directive, Member States must ensure that legal entities with 50 employees or more set up internal channels and procedures for reporting on breaches. For companies with up to 249 employees it is possible to share a reporting channel with other companies. The reporting channel and procedure must be set up to secure the confidentiality of the reporting person. It is a requirement to acknowledge the report within seven days, and give feedback to the reporting person within three months (Articles 7 to 9).

External reporting channels

Member States should encourage the use of internal reporting before going externally. However, Member States must also set up external reporting channels with relevant competent authorities which are subject to the same requirements in relation to confidentiality, receipt and feedback as with internal channels (save that feedback can, in duly justified cases, be given within six months). These external reporting channels must transmit information to relevant EU institutions (Articles 10 to 14).

Public disclosure

If a person has used the internal and external channels but no appropriate action has been taken within the required timeframes; or the reporting person had reason to believe he or she would be retaliated against because of the reporting or believes there is a low prospect of the breach being effectively addressed; or if the breach may cause imminent or manifest danger to public interest, the person reporting can be protected in cases of public disclosure (Article 15).

Protection measures

‘Reporting persons’ are protected against all forms of retaliation (including threats and attempts of retaliation, whether indirect or direct). In particular, suspension, lay-off, dismissal, demotion or withholding of promotion are referenced (Article 19). In proceedings before a court, if a ‘reporting person’ establishes that he or she made a disclosure within the framework of the Directive, the burden of proof reverses, so the employer will have to demonstrate that any detriment suffered was not because of the reporting (Article 21).

‘Reporting persons’ are also protected from liability for breaches of NDAs, and should not incur liability arising from the acquisition of the relevant information, provided that there has been no criminal offence committed (Article 21).

Penalties

Member States must provide ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive’ penalties to prevent the hindering (or attempted hindering) of reporting; taking of retaliatory measures against reporting persons; or bringing vexatious proceedings against reporting persons; or breaching duties of confidentiality. Equally, Member States should provide for ‘effective, proportionate and dissuasive’ penalties to prevent false reports or false public disclosures.

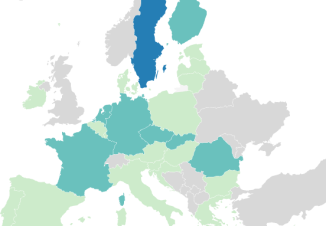

Summary of current whistleblowing legislation in European jurisdictions

Belgium

Current position

- There is no general legislation on whistleblowing in Belgium, only specific legislation on whistleblowing within federal and state (Flemish) authorities.

- Protection in place in financial services sector in light of sector specific EU directives.

- If Belgian employers decide to have a whistleblowing scheme in place they ought to follow the guidance from the Belgian Data Protection Authority.

- Employees are protected if they have registered a formal complaint because of violence, harassment or sexual harassment in the workplace. Employees will be protected for a year after the complaint is raised (in case of legal proceedings, then three months after the judgment): in this period any negative measures taken against an employee cannot be related to the complaint.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- New general whistleblower legislation will need to be enacted in Belgium.

- The statutory whistleblowing schemes currently in place will have to be adapted to meet the requirements set out in the Directive.

Denmark

Current position

- There is no general legal framework for whistleblower protection in Denmark.

- Specific legislation in place in certain sectors, for example the financial services industry, professional services industry (where transactional work is involved).

- An increasing number of companies have put in place whistleblowing schemes on a voluntary basis.

- Where an employee has reported and believes he or she has been retaliated against, the court will determine the issue on a case-by-case basis, taking into account considerations such as freedom of speech, good faith, public interest, alternative (more suitable) reporting channels.

- In Denmark, employees owe a strong duty of loyalty to their employer and this is said to limit their possibilities on reporting, particularly externally, on employers conduct.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- As no general protection in place currently, Denmark will have to enact a whole new legislative framework.

- Quite a few companies have whistleblower schemes in place, but even existing ones are likely to need to undergo some changes.

- Unions, media and civil society will push hard to secure strong protection – recent scandals may give the parliament appetite to agree.

France

Current position

- France is identified by the EU Commission as one of ten countries already having comprehensive whistleblower protection in place.

- In late 2016, general whistleblower legislation was enacted (‘Sapin II’).

- Sapin II defines the notion of whistleblowing and determines how concerns should be raised: generally, employees must report to the employer in the first instance.

- Protection is available for those who blow the whistle in good faith.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- The legislation in place in France (Sapin II) is similar to that being proposed by the Directive.

- In France, employees have to follow the priority order for reporting set out in the legislation (alert employer first, then an appropriate authority and ultimately the press). Under the Directive, an employee will be protected in some instances where he or she has reported directly to an appropriate authority or publicly disclosed.

- Under the current legislation there is a requirement for the employee not to act selfishly (out of own interests) to enjoy protection; this is likely to have to be removed in light of the Directive.

Germany

Current position

- There are no general provisions in German law governing the disclosure of unlawful activities.

- Some specific provisions are in place, for example for civil servants exposing corruption.

- Some German companies have implemented internal ethics codes including provisions regarding whistleblowing, particularly companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange with regard to whistleblowing in financial fraud matters.

- Whether the dismissal of an employee who has disclosed information is lawful is determined on a case by case basis, taking into account several factors such as: good faith, alternative (more suitable) channels in place (i.e. internal or external whistleblowing), public interest, the severity of the sanction, false or negligent statements, nature of the legal interests concerned etc.

- No requirement for employers to put in place internal reporting channels. Organisations that have whistleblowing schemes often allow for anonymous reporting.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- As there is in general no whistleblower protection in place, fresh legislation will have to be enacted; the few special regulations will need to be adapted in accordance with the Directive, if necessary. This will result in substantial changes to the treatment of whistleblowers in Germany

Ireland

Current position

- Ireland was identified by the EU Commission as one of ten countries already having comprehensive whistleblower protection in place.

- The Protected Disclosures Act 2014 provides enhanced protection for workers who raise concerns about possible wrongdoing in the workplace.

- All workers can benefit from this protection including employees, contractors and agency workers.

- Workers who make a protected disclosure can also benefit from protections from defamation claims and civil or criminal liability in certain circumstances.

- When making disclosures, a worker should ordinarily go the employer first. A worker can also go to a ‘prescribed body’ (for example the Data Protection Commissioner) if the worker reasonably believes the breach falls within that authority’s remit and the information is substantially true. An employee may, in exceptional circumstances, be allowed to disclose publically, for example to a journalist.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- There will have to be amendments to the legislation including to require companies (above the threshold) to introduce internal channels for reporting.

Italy

Current position

- Italy is identified by the EU Commission as one of ten countries already having comprehensive whistleblower protection in place.

- Employees in both the private and public sector are protected from retaliation in cases of whistleblowing.

- New legislation came into force in December 2017 to incentivise employees to report on unlawful conduct and offences.

- In the private sector, the new legislation applies to reporting on activities that can give rise to administrative liability for the company and where the offence has been committed for the benefit or in the interests of the company.

- Companies must ensure the confidentiality of the individual who is reporting and that they are protected from any retaliation. In particular, the employer must prove that any negative act (whether direct or indirect) of the employer towards the individual was not related to the reporting.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- Italy is likely to have to enact new legislation with a broader scope than under the current legislation: the scope must be broadened to include breaches of EU law and not, as now, only offences listed in the present legislation (in relation to administrative liability).

- Italy is already seen as having strong whistleblower protection and companies are for the most part already required to have specific communication channels (similar to that required by the Directive) in place.

Spain

Current position

- There is no general legal framework in place in Spain aimed directly at protecting whistleblowers.

However, such protection has been developed in Spanish case law under the framework of the so-called ‘indemnity guarantee’. This establishes that the exercise of an action at law, or of preparatory acts prior to such an action, must not carry damaging consequences for the claimant in his or her public or private relations. In the field of labour relations, the indemnity guarantee makes it impossible to take reprisals relating in any way to the exercise by an employee of his or her legal rights. This means that in the event any unjustified action is taken against a whistleblower, he or she could validly allege that this action was taken by the employer organisation as retaliation for having reported an offence within the organisation. In that case and in the event of a dismissal, the employee can make a claim for the dismissal to be declared invalid. The consequence of this would be his or her reinstatement in the job position and payment of back salary accrued from the termination date until the notification of the Court’s decision, and the possible payment of an indemnity if a violation of the employee’s fundamental rights is proven.

- Technically, there is an obligation on Spanish citizens to report criminal activity to an appropriate authority, but they cannot seek anonymity in such circumstances.

- In December 2018, the Spanish Data Protection Act came into effect and includes regulations about internal reporting channels, mainly concerning the way in which companies who decide to have a whistleblowing scheme must deal with data coming into the scheme to comply with data protection requirements. The new regulations also introduced a requirement to secure confidentiality for the identity of reporting individuals and those who are the subject of the report.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- As there is no legal framework in place for the protection of whistleblowers, new legislation will have to be enacted.

- Spanish organisations (above the thresholds) will have to establish internal channels and procedures for reporting and following up on reports with the competent Spanish authorities.

UK

Current position

- The UK was identified by the EU Commission as one of ten countries already having comprehensive whistleblower protection in place.

- The UK Public Interest Disclosure Act (PIDA) came into force in 1999 and amended the Employment Rights Act 1996.

- Under the legislation, the dismissal of an employee is deemed automatically unfair if the reason, or principal reason, for their dismissal was because they made a ‘protected disclosure’. Employees can also bring claims if they suffer a detriment for having made a protected disclosure. Compensation is uncapped.

- In the UK, disclosures are protected only if the employee reasonably believes that the disclosure is ‘in the public interest’.

What changes will the Directive bring?

- UK’s adoption of the Directive will be dependent on Brexit.

- National legislation does not require companies to set up internal reporting channels; this will have to be introduced in the implementing legislation.

- A much wider category of individuals will enjoy protection if the UK implements the Directive, for example the self-employed and shareholders.