The UK government has said that ethnicity pay gap reporting won’t be mandatory, but many employers are choosing to do it anyway, adding ethnicity pay gap reporting to their existing obligation to report gender pay gaps each year. But what about the intersection of ethnicity AND gender?

In this article we look at intersectionality in the context of ethnicity pay gap reporting. We consider why employers should think about more than just ethnicity when doing an ethnicity pay gap analysis (and more than just gender when doing a gender pay gap analysis).

There is no legal requirement for employers to report their ethnicity pay gaps. And for the time being at least, that is unlikely to change: the government has reversed a previous commitment to require employers to report their ethnicity pay gaps and is instead pushing forward with a voluntary regime. It is currently developing guidance to be published in ‘summer 2022’ for employers that want to calculate their ethnicity pay gaps.

Intersectionality is the idea that everyone has their own unique, interconnected, set of circumstances that impact them. A person’s advantages or disadvantages in work or in life can’t be explained with reference only to their ethnicity or their gender, but by the totality of all factors.

It is evident that not all straight white men are equally privileged. Some will be transgender, disabled, working class, an immigrant, and/or an older person and may experience workplace discrimination on any of those or other grounds.

In this article, we focus mainly on the intersection between ethnicity and gender and set out how employers could be approaching intersectional issues when doing ethnicity pay gap reporting.

Many employers are rightfully taking action to address their gender pay gaps, and increasing numbers are also addressing their ethnicity pay gaps. However, if these two issues are tackled separately, it risks missing out on a key piece of the diversity puzzle. A more joined-up approach is needed.

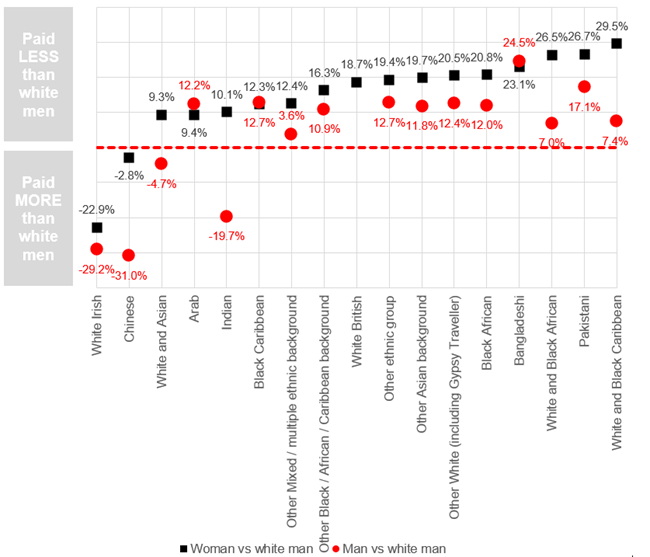

The data shows that there are important differences in the experiences of men and women of different ethnic backgrounds in the labour market. The most recent UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) ethnicity pay gap data for the UK from 2019 illustrates this.

White Irish women earn on average 22.9% more than white men in the UK. Whilst Chinese men earn 31% more on average but Chinese women only 2.8% more. Similarly, Indian men average 19.7% more than white men, but Indian women 10.1% less. Arab women average more than Arab men. Men of a mixed white and Asian ethnicity earn 4.7% more than white men on average, but women of the same mixed ethnicity earn 9.3% less. Bangladeshi men and women both earn much less on average than white men.

These figures show that not only do different ethnicities have different challenges in the labour market, but men and women do not always experience those challenges equally.

A person can bring a discrimination claim if they are treated less favourably because of their ethnicity, or because of their gender (or other protected characteristic), but not if they are treated less favourably because of the combination of both characteristics.

This is understood most easily through an illustration. If an employer did not promote a black woman because of stereotypical beliefs about black women, the affected employee would need to show that they were treated less favourably than other white employees, or less favourably than male employees, to succeed in a claim. That employee would not have a claim if she was only treated less favourably than someone with the combined protected characteristics: white men. If the employer can show it promotes lots of black employees and lots of women, it might be difficult for any claim to succeed.

The Equality Act 2010 contains an unimplemented section which would have allowed this type of ‘dual discrimination’ claim to be brought. It wasn’t implemented due to concerns that it would cause claims to become more complicated and difficult for employers to respond to. The government at the time was concerned with saving employers from ‘red tape’. There have been occasional calls to implement it over the past decade, but nothing with any great force and it is unlikely to be implemented in the near future.

To do any sort of pay gap analysis, you need a large enough group of people to analyse. If there are too few, the calculated gaps can be unstable and liable to change from year to year. Adding or removing just one or two individuals might causes gaps to vary wildly, making it difficult to establish trends and identify real disadvantages.

In addition, when looking at ethnicity pay gaps, a simple ‘white vs non white’ gap can mask differences between ethnicities; and as the graph above shows, different ethnicities have different experiences in the labour market. It is usually sensible instead to calculate gaps according to five broader ethnic groups: white, black, Asian, mixed, and other.

However, because doing this means that groups become smaller, only the largest employers will be able to then go on to segment their workforce even further so that they are able to calculate reliable intersectional gaps combining both gender and these five broader ethnic groups.

How then can employers investigate intersectional issues in their workplace?

There are options for smaller employers that want to investigate intersectional issues.

Analytical approach

Calculating adjusted pay gaps could help. This is an altogether different approach to calculating a pay gap since it allows for differences in roles. It involves creating a statistical model with the output showing what degree of impact gender has on predicting pay, when all other things are equal. This model can be extended to include ethnicity, as well as an interaction term combining both gender and ethnicity. This interaction term would reveal the extent of any intersectionality issues.

Semi analytical

Employers could calculate nine gaps, combining gender with the five broad ethnic groups and comparing against white men. However, these gaps would then need to be interpreted carefully. By this, we mean looking at the size of each of these groups and considering the specific individuals used to calculate each gap. Do not assume that a high gap is bad and a low one is good. Look closely at the data underneath the gaps. Where you identify small groups with one or two ‘outlier’ points (e.g. a newly appointed senior individual in a group of otherwise low paid employees) that may be distorting the figures, consider recalculating the gaps without them.

Qualitative approach

Speak to your staff and listen to their experiences. This might include carrying out a listening exercise or a diversity survey or an anonymous online poll (people might be more inclined to be honest if they can contribute anonymously). But less formal approaches might also help build trust and encourage your employees to confide in you, by showing you are open, listening and attentive to issues your employees want to raise.

The most thorough strategy probably involves a combination of all three approaches set out above.

People cannot be defined solely by their ethnicity or their gender; neither one taken by itself fully accounts for someone’s work – or life – experiences. Looking at the intersection of ethnicity and gender is a good start to a more holistic approach and will help ensure employers are developing initiatives and making interventions in the areas that can have an impact.

Some employers are already doing more when it comes to pay gap reporting; for instance, we’re starting to see employers calculate gaps and publish reports covering class pay gap reporting, disability pay gap reporting or LGBT+ pay gap reporting. However, many employers are looking at each of the issues in isolation and paying less attention to the intersection of protected characteristics. If intersectionality is missed from the analysis, initiatives to reduce gaps may be pulling in different directions: trying to increase ethnic diversity could reduce gender diversity and vice versa. Intersectional initiatives can therefore be an efficient way of making progress on all pay gaps. Could the future of pay gap reporting be intersectional?

For more information about discrimination