Since then, governments have imagined they have left stagflation behind, but recently, the pandemic and the war in Ukraine mean the risk of stagflation is increasing. As the economic growth rate halves in 2022, with inflation and global unemployment rates growing dramatically, that risk now is more real that it has been in decades. But how serious is this likely to be?

Countries worldwide were struggling to recover from the pandemic-related recession when the war in Ukraine created new obstacles, jeopardising the global economy and employment markets. According to a recent report published by the World Bank, in 2022, the global economic growth rate is expected to halve, dropping to 2.9 percent compared to the 5.7 percent recorded last year. The same is also true for advanced countries, where the growth rate is expected to slump to 2.6 percent from the 5.1 percent growth recorded in 2021. For example, in the EU, soaring energy prices, together with unfavourable financial conditions and trade disruptions, has reduced the economic growth rate to 2.5 percent, compared to 5.4 percent last year. Emerging markets and developing countries are expected to experience a significant drop as well, falling from a 6.6 percent growth rate in 2021 to 3.4 percent in 2022.

However, plunging global economic development is not the only adverse effect of multiple crises. In almost all countries around the world, the global consumer price inflation rate has increased significantly in 2022, with the median headline consumer price inflation jumping to 7.8 percent in April of this year.

In emerging markets and developing countries, the aggregate inflation rate has grown beyond 9.4 percent, a record level since the financial crisis in 2008. High-income countries have recorded an over 6.9 percent inflation rate, the highest since 1982.

Growing inflation and descending economic growth rates, together with unstable financial and economic conditions, increase the risk of stagflation in many countries. The type of stagflation that is a long-term threat to governments is the heady combination of high unemployment and inflation rates. The risk of stagflation currently is exceptionally high in low and middle-income countries.

World Bank President David Malpass, commenting on current economic conditions, notes: “The war in Ukraine, lockdowns in China, supply-chain disruptions, and the risk of stagflation are hammering growth. For many countries, recession will be hard to avoid.” Unpleasant economic conditions, however, not only shake the economic state of countries, but also ‘bend’ labour markets, leaving millions without a job.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the global unemployment rate is expected to reach 5.9 percent in 2022 and drop to 5.7 percent in 2023, which is still higher than the pre-pandemic level of 5.4 percent recorded in 2019. Low-income countries recorded a 6 percent unemployment rate in 2022 compared to 4.9 percent in 2019. Lower-middle-income countries jumped from a 5.1 percent unemployment rate in 2019 to 5.6 percent in 2022, while upper-middle-income countries reached 6.6 percent compared to 6 percent in 2019. High-income countries have also recorded a slight increase, reaching a 4.9 percent unemployment rate this year, compared to 4.8 percent in 2019.

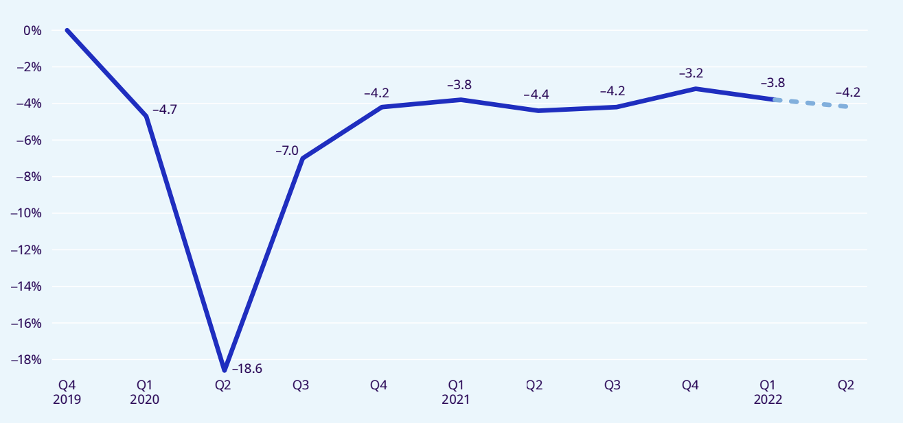

In terms of the number of hours worked, while countries recorded significant progress during the last quarter of 2021, the previous advancement fell back following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in the first quarter of 2022. At the beginning of this year, the global number of hours worked was below the level of the fourth quarter of 2019 by 3.8 percent – which is the same as a deficit of 112 million full-time positions. According to ILO predictions, the decline is expected to persist in the second quarter of 2022. This significant downturn puts the recovery of many countries at risk.

Changes in global hours worked relative to 2019 Q4 (percentage)

(Hours worked are adjusted for population aged 15–64)

At the same time, however, it is worth mentioning that advanced countries have recorded a significant employment recovery since last year – unlike developing economies. The sharp recovery of the labour market in advanced countries is partially explained by the existing tightness of the labour market, meaning a situation in which the increase in the number of vacancies is greater than the rise in the number of jobseekers.

Changes in hours worked relative to 2019 Q4

by country income group (percentage)

While the current state of world economies is challenging, economists believe growing inflation will be less disruptive than that recorded in 1970. First, in 1970, countries were more energy-intensive; therefore, the oil supply shock shook the economies heavily. Second, central banks today are more focused on targeting inflation, many with 2-3% upper limits. For instance, the US and the EU have a 2% inflation target over the medium term. Economists believe that while prices are soaring almost everywhere around the world, bending labour markets, the situation is still expected to be less painful that the shock of 1970. Let’s hope they’re right.