In many countries, there’s no specific legislation tackling isolation, as mental health is considered to be connected to the employer’s general health & safety obligations (countries where this is the case include Brazil, Estonia, the Czech Republic, Croatia and Finland). But some other places, such as Chile and Belgium, do have specific previsions. In Chile, the employer must develop a programme containing prevention and corrective measures that control, eliminate or reduce the risks. In Belgium there is a collective agreement on home working which says that the employer must take measures to prevent isolation, such as setting up regular meetings with colleagues and making sure employees have good access to the information they need – and one way to do this might include asking employees to come into the office sometimes.

General law and guidance to protect against isolation

Even if there are no specific laws, very often, there are general obligations on employers, related to a duty of care. This can mean they need to try to prevent work-related stress resulting from factors such as the nature and organisation of the work, the work environment, or poor communication by the employer. Some countries also require risk assessments that include psychosocial risks to be done under health & safety law.

There is also some guidance issued by public bodies in various countries offering suggestions. For instance, in France, a national inter-professional agreement recommends that teleworkers should be able to alert their manager to any feelings of isolation, so that the manager can offer some solutions. Teleworkers should also have the opportunity to meet regularly with colleagues and have access to company information and social activities. They should have the same professional interviews and be subject to the same evaluation policies as other employees.

Similarly, the Irish health & safety authority recommends that employees are made aware that they have support and sets out some sensible practical steps employers can take to ensure that strong connections with employees are maintained, including to:

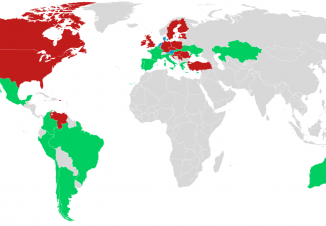

We discovered that 6 out of almost 30 countries we surveyed had specific rules relating to disconnection. This does not mean that other places have no restrictions, but in those countries, the rules tend to be either general health & safety and working hours laws or non-mandatory guidance about how to operate appropriately.

Countries with specific laws guaranteeing a right to disconnect

The question we asked our member countries was about the right to disconnect from work generally, but, of course, it is with remote work that the issue comes to the fore. Three of the countries with a specific law giving a right to disconnect are European and three are South American. This is perhaps unsurprising, as with both regions, the general employment ethos is one of benign state intervention and oversight.

In Italy, one of the 6, the right to disconnect only applies to ‘smart working’, in other words, remote working on digital devices. The law provides that smart working agreements must specify technical and organisational measures necessary to ensure the disconnection of the employee from electronic work tools. In France, teleworkers must be allowed by their employer to exercise their right to disconnect. There is no obligation on teleworkers to answer the phone or emails outside working hours or during rest periods, holidays or illness. There could even be times when employees are actually forbidden to connect, for example between 20:00 and 7:00. In Spain, new law states that the employer has a duty to guarantee disconnection, and this means limiting the use of electronic communications during rest periods and respecting the maximum duration of the working day. Employers must have an internal policy on disconnection and must train staff, including management, on the reasonable use of IT. Appropriate measures may be agreed in collective bargaining agreements.

In terms of the South American countries with specific law, in Peru, employees have the right to disconnect from their computer, phone and other means of work communication during rest days, holidays, annual leave and other periods of suspension of the employment relationship. For any employees who are not subject to the rules on maximum working time (e.g. managers and those who provide intermittent services), the daily disconnection time must be at least 12 continuous hours in a 24-hour period.

Argentina has new law, in force from 1 April 2021, providing a right to disconnect for remote workers outside working hours and during time off. Carers for children under 13, disabled or elderly people living with the carer and requiring special care, can ask for flexible working hours or a suspension of work to use to provide care. This applies equally to remote workers. Chilean law includes a right to disconnect to employees who decide on their own work schedule and those who are otherwise excluded from the working schedule limits. The legal right to disconnect provides for a disconnection of at least 12 consecutive hours in a 24-hour period, in which the employee does not have to reply to communications or employer. In addition, employers cannot make requests of employees during rest or leave.

Countries that rely on general law to provide a right to disconnect

For those countries that have no dedicated law covering the right to disconnect, many still have general health & safety and working hours rules that apply and these may largely protect them, provided the employer adheres to them.

For example, in the EU, there are strict working hours rules, including rules about breaks and rest periods and these apply equally to those working from home. Since a European Court of Justice ruling in 2019, Member States have been asked to require employers to set up an objective, reliable and accessible system enabling the duration of time worked each day by each worker to be measured. Employers who do this and therefore know exactly what hours their workers are putting in, have the data necessary to ensure no one works excessively. Having said that, we are aware that whereas Germany, for instance, is duly imposing this obligation on employers, Belgium, is not doing so. Quite where this leaves the protection of employees, particularly remote workers, in Belgium, is uncertain for the moment.

But still on the EU, on 21 January 2021, the European Parliament adopted a resolution inviting the European Commission come up with a Directive guaranteeing the right to disconnect. We will be watching that space.

Non-binding recommendations covering a right to disconnect

Examples of non-binding recommendations for employers include one from Brazil, from the Labour Branch of the Public Attorney’s Office, covering remote work. These recommend pauses in the work (with disconnection) and the courts in Brazil have traditionally treated the imposition of excessive working hours without disconnection as probable causation of occupational psychological diseases, if it involves a lack of weekly rests, holidays and vacations.

With more and more people working remotely – even as COVID recedes and office-work comes back – feelings of isolation are likely to persist, if not grow. And in terms of disconnection, the issue of how to monitor working hours and ensure people can take reasonable time to recover from periods of work are ever-present. But there is the beginnings of a trend towards specific legislation to protect workers from both of these risks and this is only likely to continue.

Sam is the CEO of Ius Laboris and you can contact him on anything to do with employment law and he will put you in touch with the right lawyer to deal with your query.